‘Work has been therapy for my mental health’

People living with a severe mental illness are very likely to be out of work – the employment rate for the group is thought to be as low as 7%. A pioneering approach is meant to change that but the NHS rollout has been slower than planned, at least in part because of Covid.

Colin Stubbings, 53, from Nottingham, says a mix of severe mental health problems, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, left him unable to leave his house.

“I couldn’t even walk into a supermarket, within a few seconds it was like a barrier had come down,” he said. “I felt like I had lost a part of myself, like I didn’t know who I was or where I fitted in society.”

Like many others, he had to give up any kind of paid work. He says he was left at home “staring at four walls, seeing blackness in my head the whole time”.

An estimated 280,000 people in the UK are living with a severe mental illness, defined as a psychological problem so debilitating that it severely impairs their everyday activities. That can include severe depression as well as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“Our target to have 55,000 people supported every year by 2024 is really ambitious. But speaking as a mental health nurse of many years, I know the importance of supporting people back to work as part of their therapeutic choice.”

Many in that category might not feel ready for paid employment. Others though would like to gradually return to the workplace. Surveys from the Care Quality Commission (CQC) suggest more than half would take a job if they were offered one.

‘Part of their recovery’

Andy Bell, deputy chief executive at the Centre for Mental Health, an independent think tank, said: “It’s not for everybody, but for many, many people getting into paid work is part of their recovery while living with mental illness.

“The evidence shows it can bring about major improvements in both mental and physical health.”

In the past, many people with severe mental illness were often deliberately shielded from paid jobs, and instead offered volunteering or part-time charity work.

A new approach was pioneered in the US in the 1990s. Individual Placement and Support, or IPS, aims to get those with severe mental illness quickly into competitive, paid employment.

Rather than placing someone in a job and walking away, the idea is that the support continues indefinitely.

Trained specialists meet regularly with both employees and employers to work through any problems, for example, removing stresses that might trigger a relapse or negotiating a different form of flexible working.

Crucially, those specialists are integrated directly into clinical teams, often sitting in the same room as the doctors and nurses who treat people with severe mental health conditions.

For the last decade, that approach has been slowly catching on across the UK, funded by a mix of NHS and local council cash.

‘Huge impact’

Clare Kerrigan, from the charity Rethink Mental Illness, which is contracted to run the employment support team in Coventry and Warwickshire, said: “In the past, most employment services got you to the front door and that’s it.

“When people come to us, they feel empowered, have a job that works for them, and are supported in their recovery. It makes a huge difference to their mental health.

“It also means more employers are also going to retain staff and ultimately less public money is going to be spent.”

The team in Coventry and Warwickshire said it’s now placing 40% of those referred into paid employment. The picture nationally though is much more mixed.

Under the NHS’s latest five-year plan for England, published in July 2019, access to IPS was meant to increase to 20,000 people per year by 2020-21. The actual number referred was 14,600, well below target, although the pandemic has disrupted the rollout.

A 2020 CQC survey of community mental health service users found that 43% of the 17,601 respondents said they would have liked support to find or keep a job but did not receive any.

Mr Bell said: “There is a patchwork of coverage and it’s often been a matter of luck if you get access to IPS, depending where you live.

“It’s really important we don’t stop until every part of the country is covered.”

NHS England said 27% of the those admitted to the scheme last year, or around 4,000 people, ended up in paid employment. It is planning to more than triple the number of people referred to 55,000 by 2023-24.

Claire Murdoch, NHS England’s national mental health director, said: “We’re really confident that we can make up what we had to pause in the pandemic, and I think we will go further, faster.”

“Our target to have 55,000 people supported every year by 2024 is really ambitious. But speaking as a mental health nurse of many years, I know the importance of supporting people back to work as part of their therapeutic choice.”

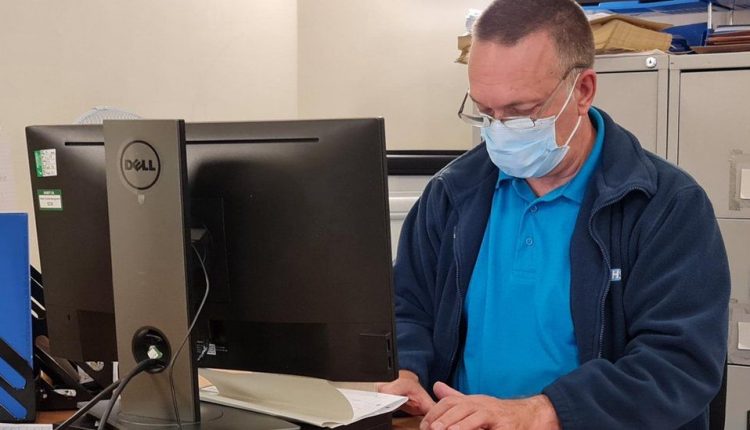

In Nottingham, Colin Stubbings was referred to the local IPS programme by his occupational therapist and has now started working in the NHS itself – first as a cleaner on hospital wards, then helping to administer vaccines. He is now applying to become a healthcare assistant.

“There are still days when I feel scared to go to work,” he said. “But as soon as I get to the front door, and I put my foot inside, I forget about everything.

“I just go and talk to people and help them where I can. It’s a big change, it’s a hard change, but it’s a good change.”

Comments are closed.