Look familiar? How rapid tests changed the pandemic

Lateral flow tests are now part of life for much of the the UK. Billions of pounds of public money have been spent on test kits. Has it all been worth it?

Earlier this week, 38-year-old Hailing Hackney unwrapped the last lateral flow test in her kitchen cupboard. “I was feeling tired, but then I’m always feeling tired,” she says. “I saw my best friend over Christmas and her son had tested positive, so I thought I should just check.”

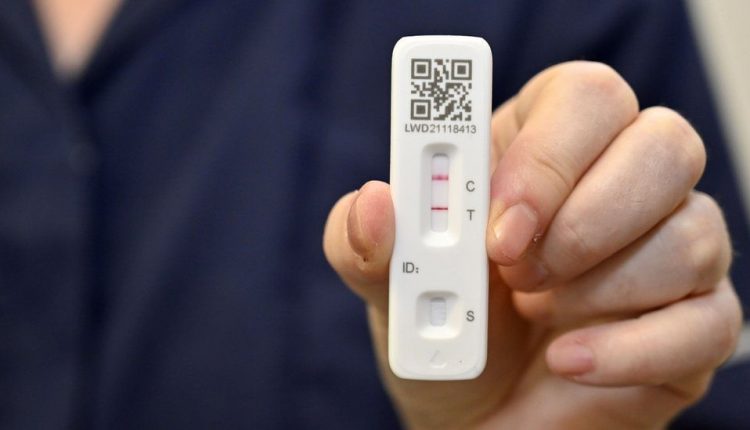

Like so many others across the UK, she was surprised when a faint line started to appear on the white testing strip. Later that evening her symptoms began – a mild headache and a runny nose.

Hailing runs Sparkle Nails & Beauty in Newton Aycliffe, County Durham. She had a full list of customers coming in for treatments after New Year and had to quickly rebook all of them.

It was just lucky I found out so quickly

“I take two tests a week because I see so many people as part of my job,” she says. “It was just lucky I found out so quickly.”

The whole point of mass testing like this is to break chains of transmission – to keep Hailing away from her customers at a time when she might be infectious but have no obvious symptoms.

“I’m serious when I say they have been the single most powerful tool in reducing transmission of the virus,” says Irene Petersen, professor of epidemiology at University College London.

The idea of population-wide Covid testing on this scale was first revealed in leaked documents in the autumn of 2020. The plan was to use millions of cheap, throwaway lateral flow tests that could give a result in 15 minutes, rather than the more sensitive PCR tests which had to be sent off and processed in a laboratory.

But Operation Moonshot – as it was called by the government – got off to a bumpy start. There was alarm about the rumoured £100bn price tag, while some of the early results of a large pilot in Liverpool raised questions about the accuracy of the tests themselves.

When twice-weekly rapid testing was rolled out in secondary schools in the spring of 2021, there were worries that large numbers of pupils would be incorrectly told they had the virus – a so-called “false positive” – and sent home. Some scientists said the school programme could do “more harm than good” and leaked emails claimed it could all be scaled back.

But data now suggests much of that concern was misplaced. Since March, 183,939 pupils in England have tested positive on a lateral flow test at home and then had a sample sent off to a laboratory for a follow-up PCR test. In total 89% of those swabs returned the same positive result.

The proportion of false positives does increase when the prevalence of the disease falls in society. But the weekly rate of those positive lateral flow tests later confirmed by PCR has never fallen below 50% and has been above 84% since the start of the school year in September.

No medical test – not even one conducted in a laboratory – can ever be 100% accurate. Some schooling was disrupted unnecessarily but – overall – those real-world results were better than some had first feared.

Alexander Edwards, associate professor in biomedical technology at the University of Reading, says it “quickly became clear” that if the tests were used as instructed, “you don’t tend to get large numbers of false positives”.

Get-out-of-jail free?

Gradually those same rapid lateral flow tests have become part of everyday life. To begin with they were rolled out in healthcare settings, workplaces and sporting events. Then in April, the programme was extended to the general public. Boxes of seven tests could be delivered free, or picked up from a pharmacy.

But false positives are not the only possible drawback with mass testing on this scale. Some scientists are concerned that the public are often far too trusting if their lateral flow test comes back negative.

“It is absolutely not a get-out-of-jail free card, and you do need to continue to take precautions like mask wearing and social distancing,” says Prof Sheila Bird from the MRC Biostatistics Unit at the University of Cambridge. “It is helping to weed out some, but certainly not all, of the true positives.”

On social media over Christmas it wasn’t hard to find posts from people who said they were clear on multiple rapid tests taken at home – even with Covid symptoms – only to test positive on a more sensitive PCR test processed in a laboratory.

Did a lateral flow test in the morning of the 6th. After 20mins a very thin (positive) second line appeared. Four subsequent LFTs were negative but I got a PCR anyway, which is positive. I’m still negative on LFTs, and symptomless, so far.

— CW (@bdylan61) January 6, 2022

An analysis of the lateral flow kit used in Liverpool showed it only detected around half of people without symptoms who – on the same day – returned a positive PCR result. But those PCRs can pick up old genetic material from the virus left in the body even after the infectious period. Prof Petersen says that rapid lateral flow tests are far better at spotting the cases most likely to pass Covid on to someone else.

A peer-reviewed paper she co-authored in October found they were 80% effective at detecting any level of active Covid infection and even better at picking up the most infectious individuals.

Quite how well lateral flow kits perform against Omicron is still unclear. Experiments showed the main brands used in the UK did successfully detect all 15 of the samples infected with the new variant. But a small study published in the past week, and based on different kits used in the US, raised fresh concerns – finding that some Omicron cases could be infectious for several days before being detected by rapid tests using nasal swabs.

Scientists say the lesson is – if possible – to test just before you socialise and think of a negative lateral flow as a solid guide rather than something that can ever rule out a Covid infection.

Was it worth it?

Health authorities budgeted £4.7bn this financial year for mass testing in England with the bulk of that going to suppliers of the kits – most of which are manufactured in China. Whether all that money is worth it is something epidemiologists are likely to be arguing about for many years. Untangling the effects of rapid testing from all the other Covid measures – from mask wearing to self-isolation – is extremely difficult and open to some interpretation.

A recent analysis of the first Liverpool pilot, which has not yet been peer reviewed by other scientists, found that the early roll out of mass testing in the city was linked to a 32% fall in Covid hospital admissions, and relieved significant pressure on the NHS. Parts of that first pilot scheme have now become government policy – for example using daily rapid tests as an alternative to quarantine for some people.

Some scientists would like to see ministers go further and use lateral flows to completely replace expensive PCR lab tests – both for those with and without Covid symptoms.

“The PCR programme is such a complete waste of resources. It’s there because it was the only thing we had at the beginning. It should be phased out sooner rather than later,” says Prof Irene Petersen at UCL.

Others think that as the Omicron wave passes, it is time to wind down the mass testing programme completely.

Allyson Pollock, professor of public health at Newcastle University, says tests should be part of a clinical diagnosis or targeted at places like care homes and hospitals, where people are working with vulnerable groups.

“The cost of mass testing has been staggering,” she says. “The best advice is if you have symptoms is to simply stay at home until you are better, and that way you will avoid spreading Covid, flu and a host of other viral infections.

“All tests create harms. Tests can give false reassurance on the one hand, and on the other can create false alarms and unnecessary isolation.”

Is testing here to stay?

Whatever happens to the pandemic itself though, scientists think mass testing may have opened the door to other more efficient ways of detecting disease in the near future. A new generation of lateral flow tests are going into production – designed to detect not just Covid but different forms of influenza and other viruses at the same time.

Some scientists think we could all soon store a supply of rapid tests or “viral thermometers” in the medicine cabinet to help diagnose sickness far more quickly.

“We have drugs which can reduce the severity of influenza, for example, but they need to be taken very soon after infection,” says Prof Alex Edwards. “You might be able to have a system where a vulnerable person can get tested and get the drugs immediately. It would be great to see a positive outcome like that from this very negative pandemic.”

Comments are closed.